Three Weeks: How to Gradually and Gently Build a New Habit

People are naturally inclined to want change from time to time. This may include the desire to take better care of health, establish a daily routine, add physical activity, learn to manage time, or simply do something beneficial on a regular basis. New habits are always connected to goals that are relevant in the present moment and to the lifestyle a person wants to achieve.

In practice, the path to a new habit is rarely easy. We often decide to start “on Monday,” but either postpone the beginning or quickly lose motivation. A few days of enthusiasm are replaced by fatigue, excuses appear, and the original intention gradually fades away. As a result, feelings of disappointment arise along with the belief that “something is wrong with me.”

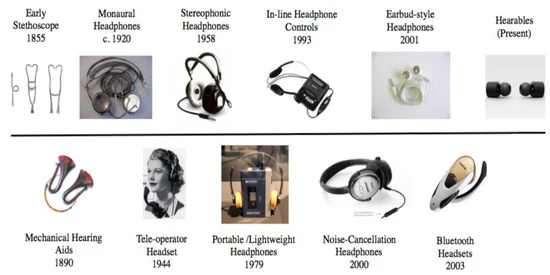

To avoid this, it is important to understand how habits are actually formed. A habit is not a one time action or a strong desire, but a stable pattern of behavior that gradually becomes almost automatic. It is reinforced through regular repetition and eventually stops requiring constant effort.

The first step always begins with a conscious decision. A person needs to honestly answer why this habit is needed, what problem it solves, and how it will change their life. Without this stage, any promise remains only a thought that is not supported by action.

Next comes the first real step, even if it is very small. A single action matters not for its result, but as a signal to the brain that intention is turning into reality. After that, repetition becomes the key factor. At first for several days in a row, then for a whole week, and later as a daily practice without skipping.

A three week period is considered the minimum time needed for a new action to start integrating into everyday life. During this time, the brain adapts to change, forms new neural connections, and the habit stops feeling foreign. If pauses occur during this period, the process rolls back each time and has to be restarted from the beginning.

The main difficulty at this stage is setbacks. They often happen not because of laziness, but because of weak motivation. Phrases such as “I must” or “I have to” rarely work in the long run. It is far more effective to clearly imagine the specific benefits the new habit will bring, the opportunities it will open, and how it will improve quality of life.

Consistency is just as important. Even a single missed day can destroy the accumulated effect. Therefore, during habit formation it is better to simplify the task and reduce the volume of actions, while preserving daily practice. Here, consistency matters more than a perfect result.

Of course, difficulties, resistance, fatigue, and the desire to give up will arise along the way. This is a normal part of change. In such moments, conscious effort and the willingness to tolerate discomfort are required. A few weeks of tension are the price paid for a long term result that will later be much easier to maintain.

In conclusion, habit formation is accessible to everyone. It does not require special abilities, only an understanding of the process, clear motivation, and discipline over a limited period of time. Three weeks of focused effort can lay the foundation for lasting changes that will work for you for years.